Has The Human Race Decimated Another Species Of Animals In A Way Similar To A Zombie Attack?

The other virus that worries Asia

(Image credit:

Getty Images

)

The death charge per unit for Nipah virus is up to 75% and it has no vaccine. While the world focuses on Covid-19, scientists are working hard to ensure it doesn't crusade the next pandemic.

I

It was 3 January 2020, and Supaporn Wacharapluesadee was standing by, pending a delivery. Word had spread that in that location was some kind of respiratory disease affecting people in Wuhan, China, and with the Lunar New year's day approaching, many Chinese tourists were headed to neighbouring Thailand to celebrate. Charily, the Thai government began screening passengers arriving from Wuhan at the airport, and a few select labs – including Wacharapluesadee's – were chosen to process the samples to try to detect the problem.

Wacharapluesadee is an expert virus hunter. She runs the Thai Crimson Cross Emerging Infectious disease-Health Science Centre in Bangkok. Over the past ten years, she'due south been part of Predict, a worldwide effort to detect and stop diseases that can jump from non-man animals to humans.

She and her team have sampled many species. Merely their chief focus has been on bats, which are known to harbour many coronaviruses.

- This story is the commencement slice in Stopping the Adjacent One – our multimedia series looking at which diseases are about likely to cause the next global pandemic, and at the scientists racing to keep that from happening. Find out more most the series, and read the other stories, here.

- Read about the new mosquito bringing disease to N America.

She and her squad were able to understand the illness in simply a matter of days, detecting the kickoff case of Covid-19 outside of China. They found that – besides every bit being a novel virus that didn't originate in humans – it was most closely linked to coronaviruses they had already found in bats. Cheers to the early information, the government was able to act quickly to quarantine patients and advise citizens. Despite being a country of nearly seventy one thousand thousand people, as of 3 Jan 2021 Thailand had recorded 8,955 cases and 65 deaths.

The next threat

But fifty-fifty as the earth grapples with Covid-19, Wacharapluesadee is already looking to the adjacent pandemic.

Supaporn Wacharapluesadee speaks with her team, which was the first to confirm a Covid-19 example outside Communist china, on a bat collecting mission in September 2020 (Credit: Getty Images)

Asia has a high number of emerging infectious diseases. Tropical regions have a rich assortment of biodiversity, which means they are likewise home to a large pool of pathogens, increasing the chances that a novel virus could sally. Growing human populations and increasing contact betwixt people and wild animals in these regions also ups the risk gene.

Over the form of a career sampling thousands of bats, Wacharapluesadee and her colleagues have discovered many novel viruses. They've mostly plant coronaviruses, only also other mortiferous diseases that tin spill over to humans. (Watch a short motion picture about the viruses that pose the greatest threat of causing a pandemic on BBC Reel.)

These include the Nipah virus. Fruit bats are its natural host. "It's a major business organization considering in that location'southward no treatment… and a high bloodshed rate [is] acquired by this virus," says Wacharapluesadee. The expiry rate for Nipah ranges from 40% upward to 75%, depending on where the outbreak occurs.

She isn't lone in her worry. Each twelvemonth, the World Health Organization (WHO) reviews the large listing of pathogens that could cause a public health emergency to decide how to prioritise their enquiry and development funds. They focus on those that pose the greatest risk to human health, those that have epidemic potential, and those for which there are no vaccines.

Nipah virus is in their height 10. And, with a number of outbreaks having happened in Asia already, it is likely we oasis't seen the last of it.

Fruit bats are Nipah'south natural host (Credit: Getty Images)

At that place are several reasons the Nipah virus is so sinister. The affliction'southward long incubation flow (reportedly as long equally 45 days, in one case) means there is ample opportunity for an infected host, unaware they are fifty-fifty sick, to spread it. It can infect a wide range of animals, making the possibility of it spreading more than likely. And it tin can exist caught either through straight contact or by consuming contaminated nutrient.

Someone with Nipah virus may experience respiratory symptoms including a cough, sore throat, aches and fatigue, and encephalitis, a swelling of the encephalon which can cause seizures and death. Prophylactic to say, it'due south a disease that the WHO would like to prevent from spreading.

Exposure is everywhere

Information technology'southward commencement light in Battambang, a city on the Sangkae River in due north-due west Cambodia. At the morning market, which starts at 05:00, motorbikes weave by shoppers, kicking up dust in their wake. Carts piled high with goods and covered in colourful sheets are perched next to makeshift stalls selling misshapen fruits. Locals wander in and out of the stands, plastic bags bulging with their purchases. Elderly ladies in wide-brimmed hats crouch over blankets covered with vegetables for sale.

In other words, it's a fairly normal morning market. That is, until you crane your neck to the sky.

The morning marketplace at Battambang, Cambodia would exist an unremarkable affair – except for its fruit bats (Credit: Piseth Morais)

Hanging quietly in the trees to a higher place are thousands of fruit bats, defecating and urinating on anything that passes below them. On closer inspection the roofs of the market stalls are covered in bat faeces. "People and stray dogs walk under the roosts exposed to bat urine every twenty-four hour period," says Veasna Duong, head of the virology unit at the scientific enquiry lab Institut Pasteur in Phnom Penh and a colleague and collaborator of Wacharapluesadee's.

The Battambang market place is one of many locations where Duong has identified fruit bats and other animals coming into contact with humans on a daily footing in Cambodia. Whatsoever opportunity for humans and fruit bats to get almost to one some other is considered a "high gamble interface" by his team, meaning a spillover is highly possible. "This kind of exposure might allow the virus to mutate, which might cause a pandemic," says Duong.

Despite the dangers, the examples of close proximity are endless. "Nosotros notice [fruit bats] here and in Thailand, in markets, worship areas, schools and tourist locations like Angkor Wat – there's a big roost of bats there," he says. In a normal year, Angkor Wat hosts two.6 million visitors: that's ii.6 million opportunities for Nipah virus to jump from bats to humans annually in just one location.

Fruit bats fly above the Battambang forenoon market, one of many locations in Cambodia where bats and humans come into close contact daily (Credit: Piseth Mora)

From 2013 to 2016, Duong and his team launched a GPS tracking programme to empathize more about fruit bats and Nipah virus, and to compare the activities of Cambodian bats to bats in other hotspot regions.

Two of these are Bangladesh and India. Both countries accept experienced Nipah virus outbreaks in the past, both of which are likely linked to drinking date palm juice.

At night, infected bats would fly to engagement palm plantations and lap up the juice as information technology poured out of the tree. Every bit they feasted, they would urinate in the collection pot. Innocent locals would pick up a juice the next solar day from their street vendor, slurp away and become infected with the disease.

Across 11 different outbreaks of Nipah in Bangladesh from 2001 to 2011, 196 people were detected to have Nipah – 150 died.

Date palm juice is also popular in Cambodia, where Duong and his team have found that fruit bats in Cambodia fly far – up to 100km each night – to detect fruit. That ways humans in these regions need to be concerned not just about being as well close to bats, only too well-nigh consuming products that bats might have contaminated.

Duong and his team identified other high-take a chance situations, besides. Bat faeces (called guano) brand for popular fertiliser in Cambodia and Thailand and in rural areas with few work opportunities, selling bat droppings can be a vital way to make a living. Duong identified many locations where locals were encouraging the fruit bats, also known as flying foxes, to roost nearby their homes and so they could collect and sell their guano.

Villagers harvest guano, a popular fertiliser in Cambodia and Thailand but one that comes with risks (Credit: Sa Sola)

But many guano harvesters have no idea what risks they face in doing and so. "Sixty per centum of people we interviewed didn't know that bats transmit affliction. In that location is nonetheless a lack of knowledge," says Duong.

Back at the Battambang market place, Sophorn Deun is selling duck eggs. Asked if she had heard of Nipah virus, i of the many risky diseases the bats could be conveying, she says, "Never. The villagers are not bothered past the flying foxes, I take never gotten sick from them."

Educating locals about the threats faced by bats should be a major initiative, Duong believes.

Irresolute the world

Fugitive bats may have been uncomplicated at ane betoken in human history, but as our population expands, humans are irresolute the planet and destroying wild habitats to meet the increasing demand for resources. Doing so is driving up the spread of disease. "The spread of these [zoonotic] pathogens and risk of manual advance with… land-use changes such as deforestation, urbanisation, and agricultural intensification," write authors Rebekah J White and Orly Razgour in a 2020 Academy of Exeter review almost emerging zoonotic diseases.

Sixty per centum of the earth'due south population already lives in Asia and the Pacific regions, and rapid urbanisation is withal taking place. According to the Earth Banking concern, almost 200 million people moved to urban areas in Due east Asia between the years 2000 and 2010.

What will the next pandemic be?

The destruction of bat habitats has caused Nipah infections in the past. In 1998, a Nipah virus outbreak in Malaysia killed more than 100 people. Researchers concluded that forest fires and local drought had dislodged the bats from their natural habitat and forced them towards fruit trees – trees grown on the aforementioned farms as pigs. Under stress, bats take been shown to shed more viruses. The combination of being forced to relocate and being in close contact with a species they would non normally interact with allowed the virus to jump from bats to pigs, and onwards to the farmers.

Meanwhile, Asia is dwelling house to almost xv% of the world'south tropical forests, but the region is also a deforestation hotspot. The continent ranks amid the highest in the world for biodiversity loss. Much of information technology is due to the destruction of forests into plantations for products like palm oil, just also to create residential areas and space for livestock.

Asia is seeing high levels of deforestation, ofttimes due to edifice plantations for products like palm oil (Credit: Getty Images)

Fruit bats tend to alive in thick forest regions with lots of fruit trees for them to feed on. When their habitat is destroyed or damaged, they observe new solutions – similar the roost of a house, or the creviced turrets of Angkor Wat. "The destruction of bat habitat and the interference of humans through hunting drives flight foxes to search for alternative roosts," says Duong. Information technology'southward likely the bats that Duong's team have monitored travelling up to 100km per night for fruit are doing then considering their natural habitat no longer exists.

Only bats, we now know, harbour a number of nasty diseases – Nipah and Covid-nineteen, but also Ebola and Sars.

Should nosotros just eradicate bats? Non unless we desire to make things much worse, says Tracey Goldstein, found director at the One Health Found Laboratory and lab director of the Predict Project.

"Bats play hugely important ecological roles," says Goldstein. They pollinate more than 500 institute species. They also help to keep insects in check – playing a hugely important role in disease control in humans past, for case, reducing malaria by eating mosquitoes, says Goldstein.

"They play a hugely important role in human health."

While bats conduct diseases, they likewise help with disease control in humans past eating insects – so culling them isn't a good option, say scientists (Credit: Getty Images)

She also points out that culling bats has been shown to be detrimental from a illness perspective. "What a population does when you decrease numbers is to have more than babies – that would make [a man] more than susceptible. By killing animals you increase the adventure, because yous increase the number of animals shedding virus," she says.

Finding answers, creating questions

For equally many answers every bit Duong and his team find, more questions are always cropping up. One is: why hasn't Cambodia experienced a Nipah virus outbreak still, given all the adventure factors? Is it a matter of time, or are Cambodian fruit bats slightly different to Malaysian fruit bats, for example? Is the virus in Kingdom of cambodia dissimilar to Malaysia? Is the way humans are interacting with bats different in each country?

Duong'due south team are working to find out the answers, but they don't know yet.

Veasna Duong and his squad still have a number of questions virtually bats and Nipah virus that they want to respond (Credit: Sa Sola)

Of course, Duong'due south team isn't lone in looking at these questions. Virus hunting is a massive global collaborative attempt, with scientists, veterinarians, conservationists and fifty-fifty citizen scientists teaming up to understand what diseases nosotros face and how to avoid an outbreak.

When Duong samples a bat and finds Nipah virus, he sends it to David Williams, head of the Emergency Affliction Laboratory Diagnosis Group at the Australian Centre for Disease Preparedness.

Considering Nipah virus is so dangerous – it is considered past governments beyond the globe to have bioterrorism potential – merely a scattering of laboratories across the earth are allowed to culture, grow and store it.

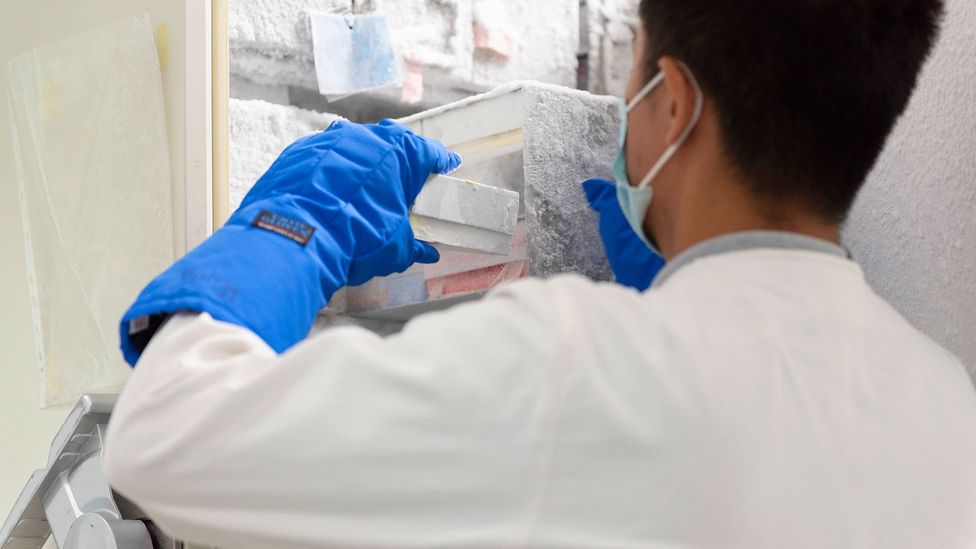

Williams'south lab is i of them. His team are some of the world'south leading experts on Nipah virus, with admission to a huge range of diagnostic tools not available in well-nigh labs. Wearing airtight containment suits, they are able to grow more of the highly unsafe virus from a tiny sample and so, working with a bigger load, to run tests to understand how it is replicated, transmitted and how it causes disease.

It'south quite the operation to become to this point: first, Duong collects bat urine by spreading a plastic sheet nether a bat roost in Cambodia. This avoids having to catch the bats, which can be traumatising for them. He takes his samples back to the lab, decants them into tubes, labels them and packs them safely into cool boxes. These are collected by a special courier who is approved to ship dangerous appurtenances and flown to Commonwealth of australia, where the virus samples pass through customs to have the accompanying licenses and permits approved.

1 of Duong's team works with a sample of bat urine (Credit: Sa Sola)

Eventually they arrive at Williams's lab. Later testing, he'll share the results with Duong dorsum in Cambodia. I ask Williams if building more high-security labs like his across the globe might speed up the detection of harmful diseases. "Potentially yes, by putting more than [biosecure] labs in places like Cambodia that could speed upwardly characterisation and diagnosis of these viruses," he says. "Withal, they're expensive to build and maintain. Often that's the limiting element."

Funding for the piece of work that Duong and Wacharapluesadee are conveying out has been patchy in the by. The 10-year Predict plan was allowed to expire by the Trump assistants, although US President-elect Joe Biden has promised to restore it. Meanwhile, Wacharapluesadee has funding for a new initiative chosen the Thai Virome Project, a collaboration betwixt her team and the government'south Department of National Parks, Wildlife and Constitute Conservation in Thailand. This will let her to sample more bats and a wider range of wildlife to empathise the diseases they harbour and the threats to human health.

Duong and his team are searching for funding for their next pathogen detection trip – one to back up the continuous surveillance of bats in Cambodia and to understand if there accept been so-far-unreported infections in humans.

Duong's team are currently searching for funding for their next pathogen detection trip (Credit: Sa Sola)

They take not yet managed to secure the money to go on their Nipah virus work. Without it, they say, a potentially catastrophic outbreak is more probable.

"The long-term surveillance helps the states… inform authorities [to enact] preventive measures and to prevent undetected spillover which would cause bigger outbreak," says Duong. And without connected training, scientists might not be able to identify and characterise new viruses rapidly, every bit Wacharapluesadee did with Covid-19 in Thailand. This information is needed to start working on a vaccine.

When we spoke in June 2020 via video call, I asked if Wacharapluesadee was proud of her squad's remarkable achievement. "Proud?" she said. "Yep, I am proud.

"Only the Predict project was an exercise on how to diagnose novel viruses from wildlife. So when me and my team found the genome of the [coronavirus pathogen] it'southward non likewise much [of a] surprise, because of the inquiry project. It gave us a lot of experience. It strengthened our capacity," she said.

Duong and Wacharapluesadee promise to continue collaborating to fight Nipah virus in South East asia, and the pair have drafted a proposal for Nipah virus surveillance in the region together. They plan to submit it to the Defence Threat Reduction Agency, a US governmental organisation which funds work aimed at reducing the threats posed by infectious disease agents, one time the Covid-19 crunch subsides.

In September 2020 I asked Wacharapluesadee if she thinks she can stop the next pandemic. She was sitting in her office in her white lab glaze, having processed hundreds of thousands of samples to test for Covid-19 in the past months – far beyond the usual capacity of her lab in any more than usual year.

Despite information technology all, a smiling broke across her face. "I will endeavour!" she said.

With boosted reporting by Mora Piseth in Cambodia.

Reporting for this story, part of our series Stopping the Next 1 , was supported with funding from the Pulitzer Eye.

--

Join i million Futurity fans past liking usa on Facebook, or follow u.s. on Twitter or Instagram.

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called "The Essential List". A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Civilisation, Worklife, and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.

Source: https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20210106-nipah-virus-how-bats-could-cause-the-next-pandemic

Posted by: simpsonderignatim.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Has The Human Race Decimated Another Species Of Animals In A Way Similar To A Zombie Attack?"

Post a Comment